Is there too much political correctness in the world, asks Nesrine Malik in new book

"The protest is an infringement of free speech."

"Look how far women have come; the battle for gender equality is over."

You'll have no doubt heard a version of these in real life, or seen words to their effect pass your phone or computer screen while scrolling through social media. But is there too much political correctness in the world?

Is protesting, say, the invitation of a speaker with extreme, hateful views an infringement on his and the audience's right to freedom of speech? And is feminism now going too far?

The answer to those questions, according to journalist Nesrine Malik, is no, and she makes a compelling case for her viewpoints in her book We Need New Stories.

The book takes what Malik considers to be the "six most influential myths behind our age of discontent": the myths of gender equality, the crisis in political correctness, the free speech crisis, damaging identity politics, virtuous origin and the reliable narrator.

Malik devotes a chapter to understanding the origin of each myth, and why and how we need to create a new myth in its place.

None of the myths Malik examines are new, but the way they are used and disseminated – widely, over the internet – is.

|

|

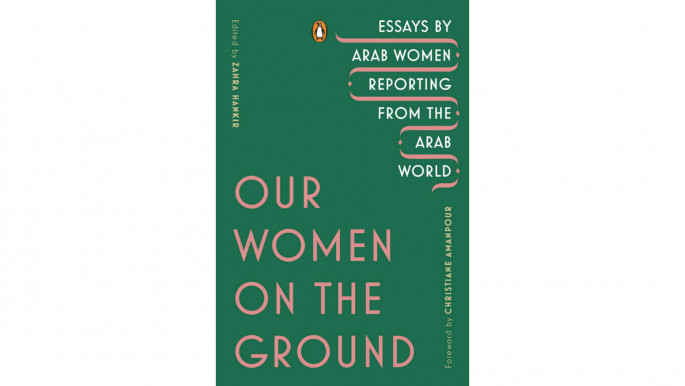

| Read more from The New Arab's Book Club: Our Women on the Ground: At last, recognising the heroism of Arab female journalists |

This is particularly true for discussions on free speech, given that we're currently in a time and place where anyone can access an audience via social media. The right to freedom of speech is equated, by those arguing that the right is being eroded, to having the right to a platform to say whatever you want, even if you're inciting hatred.

The political correctness myth also functions in a similar way, with dominant voices who want to be able to do or say whatever they like, without consequence, shouting that it's "political correctness gone mad" if they aren't given the permission to do so, or if they are asked to be sensitive towards another group of people.

"The moment these requests for sensitivity are made, they are, according to the establishment, immediately too much," writes Malik.

"Whether it was the civil rights movement in the United States in the 1960s or the request that new non-white authors be included in British university syllabuses in 2018, the most tentative steps towards redressing imbalance are always seen as going over the top."

It's the chapter on the myth of virtuous origin – the idea that some history is erased to present a favourable image that can be celebrated – that is the best in Malik's book.

Born in Sudan and spending most of her life up to the age of 25 living in the Arab world, Malik recounts how she only found out about the storming of the holy mosque in Mecca after moving to Europe, because it's not something taught or talked about in Saudi Arabia.

Of course, Saudi Arabia is not the only place to have a curricular blind spot; the UK doesn't teach empire in schools, and when the era is portrayed on television, it's usually romanticised. This creates, as Malik points out, a literal myth about the UK's history.

"By glossing over the detail and omitting the legacy of imperialism, the British approach toward history is defensive, inevitably dishonest and ultimately delusional," she writes.

Part-history, part political, social and social history, and part personal story, We Need New Stories is meticulously researched and written, with Malik building her arguments carefully point by point, until you wonder why these myths are still peddled.

But of course, the why is a large part of the book. In the chapter on the myth of the reliable narrator, Malik argues that the myths she has previously called out stand because of those who strengthen them.

"How can you separate lazy rote thinking on freedom of speech from its instrumentalism by bigots and hate preachers?" she asks. "How can you separate a hardwired belief in the superiority of a national's values from the bigotries that engenders? You cannot. The myths need narrators."

Malik's chapter on reliable narrators calls out those who have made a career out of reinforcing these myths, from historians to journalists, arguing that we need not just new myths, but also new narrators. Malik herself is one of those new narrators, battling the defensive, dishonest and delusional myths that offer a frame of reference for the world we live in with insightful, courageous and important alternatives.

Sarah Shaffi is a freelance literary journalist and editor. She writes about books for Stylist Magazine online and is books editor at Phoenix Magazine. She is a judge for the Jhalak Prize 2019. Sarah is editor-at-large at independent children's publisher Little Tiger Group. She regularly chairs author events, and is co-founder of BAME in Publishing, a networking group for people of colour in publishing.

Follow her on Twitter: @sarahshaffi

The New Arab Book Club: Click on our Special Contents tab to read more book reviews and interviews with authors: