Morocco's Sidi Moumen Cultural Centre: Changing futures and perceptions

Rows of uniform, beige and white-coloured apartment blocs stand side-by-side, laundry hangs from most windows and balconies, while pedestrians dart between the traffic.

And yet amid the cacophony one morning in mid-October, the Sidi Moumen Cultural Centre stands out.

A bright, blue basketball court fills most of the courtyard in front of the building, which is ringed by low walls covered in paintings and graffiti.

"Never give up," is scrawled on a trailer that serves as a workshop where local women learn to sew. Next to it is written "We love you, Morocco", in Arabic, and a map of the North African country.

Inside, two young teachers wrangle toddlers into their seats to have snacks and listen to a tape, while the youngsters clamour over one another to get the best toys off the shelves.

"This community is my family," says Soukaina Hamia, deputy director of the centre, and one of its first pupils. Now 30, Hamia was involved with the centre from about the very beginning 10 years ago.

"The parents, the children, they feel that the centre is theirs. It's not in an egoistic way, but it's yours, so you care about it. I feel it's mine. It's something that's very, very dear to me, like a child," Hamia told The New Arab.

|

| A bright, blue basketball court fills most of the courtyard in front of the building |

Disenfranchised youth

Sidi Moumen made headlines in 2003 after a series of deadly suicide bombings at various locations in Casablanca were traced back to young men from the neighbourhood.

That's when Boubker Mazoz decided that something had to change.

At the time, Sidi Moumen counted around 350,000 residents - today that number is over half a million - and 75 percent of the population was under the age of 25, Mazoz said.

But there was no "safe space where they can get together, be tutored, learn, study".

The neighbourhood is referred to as a slum, or bidonville, where poverty and unemployment are rampant, and services and opportunities are few.

"Where do they go? They are of course easily trapped by delinquents, drug dealers, criminals and extremists," Mazoz told The New Arab.

He founded the Sidi Moumen Cultural Centre, the first community centre ever opened in the Sidi Moumen, in 2006.

But it wasn't easy at first to draw in students, especially as an outsider not originally from the area, Mazoz said.

But after recruiting local youth to join, and training them to be leaders themselves, local families became more comfortable and willing to bring their children to the centre in those early years.

Now in its 10th year, the centre now counts more than 300 students, and must turn would-be participants away due to lack of space.

|

All the people working here are from the neighbourhood, with the exception of a few. - Boubker Mazoz |

|

From toddlers and primary and high school students to adult women, the students come for language, music and theatre courses, sports and other activities.

"I am actually working with the youth of the neighbourhood and elevating them to the level to becoming leaders in their community," Mazoz explained. "Now, all the people working here are from the neighbourhood, with the exception of a few."

|

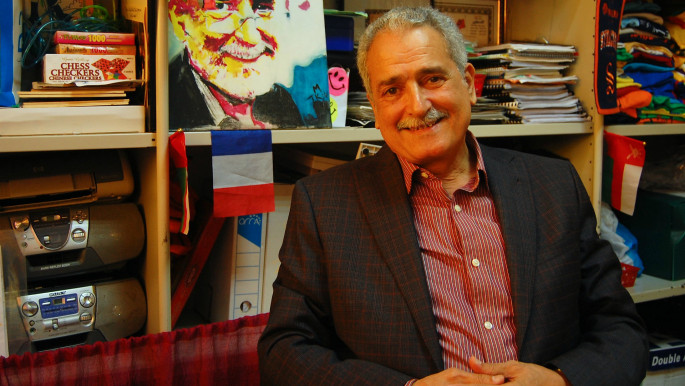

| Boubker Mazoz founded the first community centre ever opened in the Sidi Moumen in 2006 |

Lack of volunteerism

Hamia readily admits that she was sceptical of the idea at first.

She said volunteerism is a foreign concept in places like Sidi Moumen, which is often described as a slum, and which, despite major improvements in recent years, still suffers from misconceptions and stigmatisation.

"When we started, we had great difficulty convincing people to teach languages and volunteer, but now, even people who weren't convinced in the beginning, they're the ones who manage the centre. And I'm one [of them]," she said with a laugh.

"But they don't know that what you learn and what you take from the experience is really much more than what you give," Hamia said about the experience of volunteering.

For Mazoz, while changing peoples' perceptions about Sidi Moumen is important, it is even more critical to instil a sense of pride in local youth.

Recently, a youth singing group from the centre was invited to perform on a Moroccan television program, he recalled, "and they were so proud to say, we are from Sidi Moumen".

"They were about 30 of them, and they sang beautifully – chest out, heads up, eyes open and looking at the people. And that's what we wanted them to do: it's to regain this confidence in themselves and regain of course with it their dignity."

Ten more centres

Mazoz also heads the Casablanca Chicago Sister Cities International partnership, through which Moroccan youth have travelled to the United States, and vice-versa.

The centre also has a partnership with Syracuse University, in which participants take arts, culture and storytelling courses, and a school-to-school program with an institution in Grand Rapids, Minnesota.

Mazoz said more than 100 volunteers join the centre annually from around the world to teach the students.

Now after 10 years in Sidi Moumen, Mazoz said he hopes to open 10 similar centres across Morocco, including two more in Casablanca.

The goal, he said, is the same it was a decade ago: to provide the country's youth with options other than getting involved in petty crime and drugs, joining extremist groups, or leaving Morocco altogether, and address their disenfranchisement head-on.

"There is a lot of empty time, and spare time, for the kids [to] have nothing to do. [They] have no possibility to even stay in their homes. They are squeezed in the homes. They don’t feel like they are living," he said.

"We don't want people to try to cross the Atlantic to kill themselves, thinking they can reach El Dorado, or people to go and join the extremists."