Syria's 'lost generation' makes reconstruction 'very difficult'

The report Nowhere Left to Go: Syrian Refugees Head to Europe traces mass migration from Syria to 2012, following the militarisation of the Syrian revolution, at which point the Syrian regime adopted what the report described as “scorched earth” policy of collective punishment against the residents of towns not under its control.

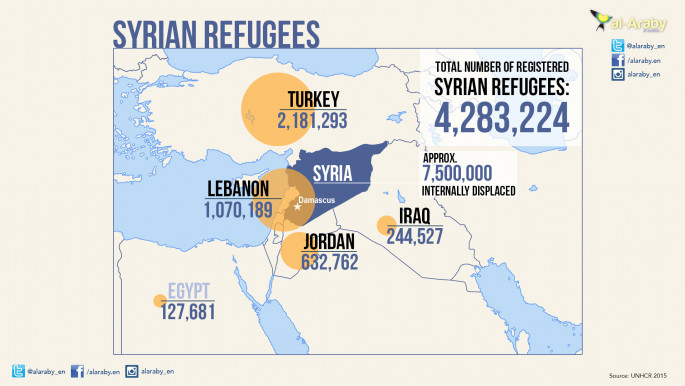

| There are four million Syrians refugees outside Syria, out of a pre-war population of 21.9 million. |

There are at present about four million Syrians refugees outside of Syria, a "staggering number" say the authors, out of a pre-war population of 21.9 million.

Europe not the first choice

At the start of the war, migration to Europe was limited to only well-to-do Syrians, civil society activists, relief and aid workers, those who were already studying or working in the European Union and those who had managed to secure official recognition of their refugee status.

The number of Syrian refugees who sought safety in Europe between the outbreak of the Syrian revolution and January 2014 was approximately 90,000, says the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Most Syrians sought safety in neighbouring states such as Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon where they waited to return to their home country once a resolution to the crisis could be found.

|

|

| Click on the image to enlarge |

Egypt during the rule of former President Mohammed Morsi was also an attractive destination for well-to-do Syrians, thanks to several factors - amongst them reciprocal arrangements that gave Syrians the same access as Egyptians to health and education services.

These measures as well as streamlined residency plus the comparatively low cost of living in Egypt, all acted as a pull factor.

But the number of refugees seeking asylum grew rapidly in 2014 as it became clear that the principles stated in the final communiqué of the Geneva II conference on Syria would not be honoured and a negotiated resolution to the Syrian conflict was unlikely.

By then, Syrian refugees began heading for Europe because living conditions in Jordan, Lebanon, and Egypt were deteriorating.

The reduction in UN support for Syrian refugees in these countries exacerbated this situation, particularly as it relates to the education of refugee children and healthcare for the refugee population in total.

By contrast, Germany expressed an expectation that it would take in 800,000 refugees by the end of 2015.

These stark realities as well as the expansion of the so-called Islamic State group in Iraq and the Levant into Kurdish inhabited areas such as Kobane pushed a greater number of Syrians to leave the region.

'A lost generation'

| Unlike the countries neighbouring Syria, refugee status in Europe implies an eventual integration and naturalisation as citizens. |

For most Syrian refugees, the chance to seek asylum in Europe holds out the prospect for a solution to the suffering they have endured since 2011.

The chance to settle in Europe means, to them, some peace of mind, a chance for their children to receive an education, and the opportunity to work, not to mention other individual benefits.

Unlike the countries neighbouring Syria, refugee status in Europe implies an eventual integration and naturalisation as citizens.

Ultimately, these steps will make it less likely that these refugees will return home.

If the present pace of emigration from Syria continues, the report asserts that it is likely that hundreds of thousands of its citizens will flee the country in the coming years.

Western officials have expressed plans to integrate Syrian refugees over the next five years; these statements serve to heighten anxieties that Western countries aim to prolong the Syrian crisis itself, choosing to focus solely on the human rights aspect of it.

A long-term European accommodation with the refugee crisis would lead to a demographic disruption in Syria that would be no less severe and consequential than the Damascus regime’s orchestrated campaign to force its own people out of the country.

This most recent wave of migration has decimated Syria’s middle classes: the evidence suggests that those Syrian refugees leaving to Europe today are not the wretched of the Earth, otherwise consigned to the squalor of refugee camps, but rather come from the educated professional classes.

Their motivations to reach Europe are related, in large part, to their desire to find stability and a secure livelihood for their families.

A recent report carried by Swedish broadcaster SVT illustrates this reality: Syrian refugees who arrived in Sweden in 2014 and who were granted indefinite leave to remain had the highest educational attainment of any group of refugees living in the country.

The authors of the research warn that what they called "the haemorrhage" of the Syrian population will have a major negative impact on the future of Syria, making the process of post-conflict reconstruction more difficult.

The report concludes that it seems likely that Syria will lose an entire generation of its youth, who are now likely to grow up in a cultural environment that is different from that of their home country and in which they will gradually be stripped of their cultural identity.

This will have implications for Syria as much as it has for their future loyalties and priorities.

![Syrians refugees [Pic used - dont reuse] Syrians refugees [Pic used - dont reuse]](/sites/default/files/styles/large_16_9/public/media/images/A0925D89-D1DE-47B6-8788-FCCB8C6119F1.jpg?h=d1cb525d&itok=AWD-cDOa)