The revolution will not be funded, but that won't stop her

When women make up half the bodies on earth, you expect that parity to be represented all around us – as leaders and as learners. On a global scale, the UN says we're not there yet, on a national level, the government agrees there's more work to do. Turn that lens on to local communities of colour then the challenges are specific, intersectional and often missed.

Unless you're Farzana Khan, who at 28-years-old is the creative and strategic director of youth programme Voices That Shake! As a Bengali Muslim growing up in Tower Hamlets she was galvanised by the targeting of her community by the Prevent programme. She now teaches young people to question and challenge the establishment through film and art. And despite being told her work has been disruptive by one funder, she continues to navigate the funding cuts to keep the organisation going.

I meet her in a space near Liverpool Street, London in the heart of Britain's finance sector that happens to have a lowkey row of art galleries among the side streets. It's a world away yet a stone's throw from where she grew up.

Khan's been working in the youth space since her mid-teens, initially within council estates and knows full well the challenges facing young people and women of colour, who are Muslim, working class or are from the LGBTQ+ community. By the time she was 20, she was receiving commissions to develop her own programmes, becoming recognised for her art-focused methodology that helped young people bridge social issues they were affected by.

Come 2015 a lot of her work shifted to work with young women who'd experienced gender and sexual violence, shaping a raison d'être going forward.

|

|

| Read also: Women like us: British Muslimahs resist |

"The Eurocentric or white methods of mental health and well-being were inadequate," Khan said she found, adding that "often these mental health services were sites that reproduced harm for marginalised communities."

Working class or women of colour would fear their kids being taken into care, or some other type of state intervention when trying to access health services. The institutional infrastructure was so inadequate that Khan's work focused on what holistic culturally sensitive, spiritual, indigenous tools could then be used to redress the trauma experienced by these women and prevented further isolation or harm.

Without redressing this type of gender-based violence and harm, at an institutional level, then you can't begin to think about gender justice within those institutions; and Khan very much prefers the term 'gender justice' than feminism, as she explained to The New Arab.

"Gender justice honours the spectrum of gender identity. [It] holds the scale of violence and brutalisation that patriarchy does to all of us female, male… queer etc."

|

The Eurocentric or white methods of mental health and well-being were inadequate, Khan said she found, adding that often these mental health services were sites that reproduced harm for marginalised communities |  |

Questioning society is a key part of what Khan includes within her methodology because she says the harm inflicted on young women and young people of colour is often at the hands of the state itself.

|

|

| Farzana Khan is the creative and strategic director of youth programme Voices That Shake! |

This not-always-popular view adds an extra challenge to funding – in fact, one of its early funders pulled away after Shake!'s bid for support with a film exploring state violence in their communities. They deemed it too radical and disruptive to the status quo, but it's the status quo Khan says is detrimental, fatal even, to some communities.

That's why through her work with Shake! Khan has helped continue projects covering issues like gentrification, police brutality and the harm experienced from colonialism including through arts, film and activism, work which has been recognised by virtue of its Alumni accomplishments – Selina Nwulu was London's Poet Laureate and others have had films reach festivals and receive awards, such as the 2013 film REACH, which depicted the contrast between wealth and poverty in communities around London and was shortlisted for a Small Axe Radical Short Film Award. And Surviving the State, a film that looks at the relationship between youth violence and gentrification was screened at the East End Film Festival in 2018.

Outside of Shake! one of the projects to support young women and young people of colour to "undo harm, heal and regenerate," is through an organisation called Healing Justice London, co-founded with other women of colour living in London, which is where some of those indigenous and spiritual tools kick in.

What that looks like can be meditative and reflective exercises, theatre-based and embodiment work – addressing different forms of harm like microaggressions, class violence, power privilege dynamics or survivor guilt. As Khan says, for those to have the most impact on the frontline they have to have opportunities to show up as the best versions of themselves.

Khan's approach has been informed by her master's thesis on "radical education," for the sake of democratising or levelling power. Although there is a much deeper story as Khan's life is one that's forced her to be aware of her own political consciousness and practice.

|

Questioning society is a key part of what Khan includes within her methodology because she says the harm inflicted on young women and young people of colour is often at the hands of the state itself |  |

Growing up on a council estate in a London borough known for its heavy Muslim demographic, Khan remembers a childhood full of community, joy and play, being one of six siblings. But also, one she said was impacted by "state harm."

"If you live in Tower Hamlets, are a person of colour, working class and Muslim, it becomes very clear that you're living under Prevent," she says in reference to the controversial UK counterterrorism programme. The policy burdens people in authority like teachers or doctors to recognise potential signs of radicalisation and inform the government. In many cases, they're then flagged to go through a de-radicalisation process.

Then the far-right nationalist English Defence League started marching in 2013 and Khan became aware of the sense of not belonging felt by many young people she supported.

Read also: Call security measures by their name: Racial discrimination and Islamophobia

A number of elements in Khan's life started to come together. Working overseas, such as within refugee camps of Lebanon, she refers to the development world's white saviour complex, while also having been well-educated, she was being exposed to spaces of extreme privilege and gaining a metaphorical seat at the table. With these elements of exposure, she came to realise that the social work sector to which she was devoting her life "wasn't representative of working-class folk. It wasn't representative of Muslims, it wasn't representative of Black and Brown folk and a lot of those [underpinning] narratives were actually false and causing harm."

|

|

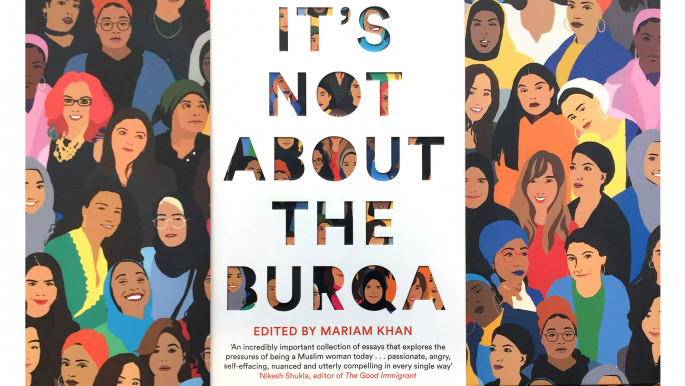

| Read also: It's Not About the Burqa: It's about letting Muslim women speak |

It's through projects like Voices That Shake! and her other bodies of work, that she looked to address this lack of representation and start to disrupt the status quo that's presented its problems with resourcing. While Shake! does have some funders, Khan realises that, "The reality is the revolution will not be funded, the master's tools can't build our house." Hence, she looks forward "to building alternative economies and ecologies rooted in justice and thriving."

In the UK, the youth sector has experienced cuts in government funding by 62 percent, from just over £1 billion in 2008-09 to £388 million in 2016-17, and it seems to be going in a different trajectory to many other countries.

Anya Satyanand, Chief Executive Officer of the Princes Trust New Zealand, told The New Arab that in other countries across the Commonwealth, you're in fact starting to see progression in terms of youth workers gaining professionalisation, which can be important in terms of reconciling gender and power, "Sitting at the heart of youth work is this focus on rights and empowerment."

Danielle Williams is a professional youth worker from Bromley in southeast England but says of traditional practice that "social justice isn't necessarily embedded in the way that I view social justice." Williams was drawn to the notion of helping young people understand their political climate, so she attended a Healing Justice workshop. When it comes to implementing what she has learned in traditional youth work, Williams admitted it would be a "process."

That's the challenge Khan faces, not just in terms of funding but wider acceptance even if she believes hers is the radical trajectory needed to start building a more equal world.

Sophia Akram is a researcher and communications professional with a special interest in human rights particularly across the Middle East.

Follow her on Twitter: @mssophiaakram