Murder, tax-evasion, cronyism: Yemen's 'Sugar Kings' implicated in #PanamaPapers

A New Arab investigation based on the Panama Papers can reveal how hidden companies controlled by the Abdulhak empire have used tax havens and offshore fronts to dodge taxes in Yemen.

The investigation tracks down secret dealings by the Abdulhak family through both known and hidden companies, acting as fronts for powerful entities in Yemen to launder money and evade taxes without facing legal repercussions.

While the Abdulhak brothers control key businesses in Yemen - enabled and facilitated by their ties to Saleh - their investments span almost the five continents, working in sectors including telecomms, oil, tourism, construction and import and export.

Despite being wanted by the authorities in Britain and Norway for questioning in connection with his son Farouk's alleged rape and murder of Martine Vik Magnussen, a Norwegian woman and daughter of another billionnaire, Shaher Abdulhak remains at the helm of his family's empire out of Sanaa, thanks to the safe havens of the Caribbean and the European continent.

The Abdulhak group owns a number of offshore companies registered in the British Virgin Islands, the New Arab investigation discovered.

The group uses these companies, many of which are shell companies that have been registered offshore for many years, to apply for and win government tenders that usually require bidders to have years of experience in their original countries.

The offshore shell companies are also used to conclude sham contracts with their original companies in Yemen to transfer money into havens overseas, to avoid paying profit taxes.

The New Arab’s request for comment was not answered by the Abdulhak group, despite repeated emails and reminders of the date of publication.

| Read more: All the dictator's men: Who runs Assad's sanctions-busting network? |

Following the trail

The authors of the investigation examined hundreds of documents, and thousands of emails leaked from offshore consultancy Mossack Fonseca, obtained by The New Arab in partnership with the ICIJ, Germany's SZ daily, and ARIJ.

|

|

| [click to enlarge] |

The brothers Abdulhak own 18 offshore companies in the British Virgin Islands, according to registration documents issued by German and Egyptian banks. Some of these companies have the same name as their Yemen-based counterparts - such as JabalSalab and Sheba.

Thanks to this loophole, the brothers' assets are safely tucked away, far from the reach of the Yemeni authorities, should they decide to freeze or seize them. They can also avoid money laundry investigations and enjoy more financial flexibility, according to legal sources consulted by The New Arab.

These companies are managed by foreigners and ostensibly owned these partners, some of whom were named in the documents as Linda Blampied, James Wetherall and Julian Griffiths. However, the same documents show the brothers Abdulhak and their subsidiary companies as the real or "beneficial owners" of these companies.

According to documents obtained by The New Arab, 14 of the 18 offshore companies work overtly.

The authors tracked down the data of all offshore companies owned by the brothers, led by the JabalSalab company. JabalSalab is mainly involved in oil prospecting and mining in Yemen, Somalia and Ethiopia, where it has routinely bid for oil exploration tenders.

JabalSalab's offshore mirror, registered in the Virgin Islands, is a British-Yemeni company based in Sanaa. Shaher Abdulhak owns 48 percent of its shares.

|

A pattern of cronysim emerges from Yemen to Sudan, favouring the Abdulhak empire |  |

Transcontinental cronyism

The same pattern is repeated with the rest of the group's companies, such as the Sheba Investment Holding Limited (oil and tourism), based in Ethiopia; and Shaher Trading overseas limited.

Shaher has branches in Yemen, Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia. It operates in banking, telecomms and oil. It is also understood to monopolise representation of international brands in Yemen such as Coca Cola, Mercedes Benz and Xerox. It is registered offshore.

This company in particular was given more than a helping hand from the regime of deposed President Ali Abdullah Saleh. For many years, Shaher Trading won contracts with the Yemeni Defence Ministry to procure German armoured vehicles as well as long-term maintenance and supplies contracts, according to documents leaked from the ministry in December 2012.

The cronyism does not stop at Yemen's borders.

In Sudan, an Abdulhak subsidiary named BashairTelecom SA was awarded a mobile phone operator license in 2003, but when Sudanese newspapers leaked the names of 13 other companies that came ahead of BashairTelecom, a scandal erupted.

The company was not among the declared winners, and was added after the tender deadline. The Sudanese government claimed the company was chosen for paying 150 million euros for the license, while other companies offered much less.

Again, despite having foreign owners, the beneficial owner of this company is none other than Shaher Abdulhak, according to the documents.

Tax evasion

The investigation analysed hundreds of documents issued by authorities in tax havens and by international banks, as well as emails sent by the managers of offshore companies associated with the Abdulhak brothers, to make some interesting revelations regarding transfer of shares and funds.

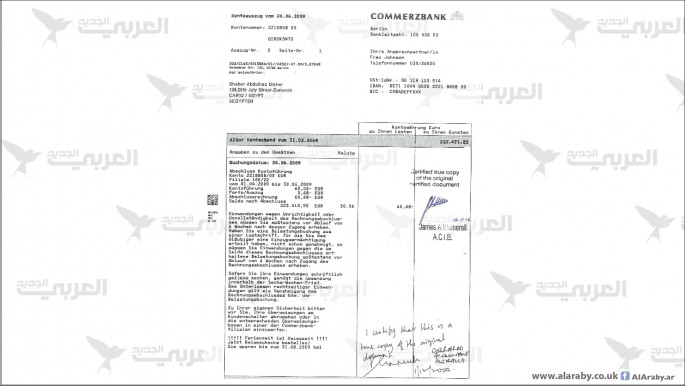

A bank statement on behalf of Shaher Abdulhal, dated 30 June 2009, issued by the CommerzBank in Germany, possibly links the brothers to tax evasion.

The bank, the second-largest in Germany, was linked last year to a scandal related to helping clients avoid tax and conceal funds in their home countries.

In 2013, an officer at Yemen's central bank leaked a list of 522 Yemeni companies and commercial entities that had defaulted on their debts, which were, as a result, classed as bad debt - meaning they could not be recovered.

Shaher Abdulhak, despite his vast wealth, holds the lion's shares of these unpaid debts, through companies such as Shaher Trade, JabalSalb, and others he owns.

The offshore connection also allowed the Abdulhaks to circumvent court orders, for example in a dispute over the ownership of the Mercedes Benz dealership in Yemen, according to the other party in the dispute, Mohammad al-Safari, who spoke to The New Arab.

|

Farouk Abdulhak, son of Shaher Abdulhak, is the only suspect in the murder of Martine Magnussen |  |

Who killed Martine Magnussen?

In March 2008, police found the body of Martine Magnussen, a Norwegian woman, in the basement of an apartment block, hidden under rubble, in a block of flats in London's Great Portland Street. She had been strangled to death.

Farouk Abdulhak, the son of Shaher Abdulhak, is reportedly the only suspect in the case, being the last person with whom she was seen alive.

Farouk fled Britain for Egypt hours after her disappearance, on a private jet belonging to his father, before flying on to Yemen, where he had the protection of the government, according to British and Norwegian investigators.

Ali Abdullah Saleh's government refused to extradite him. Later, Saleh's foreign minister reportedly tried to persuade British authorities to stop their legal action against Farouk. In 2010, the Yemeni authorities also prevented a Norwegian journalist from entering Yemen to further investigate the case.

The case caused huge problems for Shaher Abdulhak, who even attempted to pay blood money to the victim's family, which rejected it.

In 2011, Coca Cola said it had stopped dealing with Shaher Abdulhak following a boycott campaign launched by Norwegian activists, but registration details on the company's website show Shaher's brother, Abduljalil, as the current manager of the company that holds the local franchise.

|

Western media call Shaher Abdulhak 'the king of sugar', for his involvement in the soft drinks industry |  |

The Sugar Kings of Arabia

Western media call Shaher Abdulhak "the king of sugar", for his involvement in the soft drinks industry. In addition to being a personal friend of Ali Abdullah Saleh, he also acted as his personal envoy in secret missions, most recently to Muammar Gaddafi in 2011.

The visit was denied by the Yemeni government, but Libyan TV broadcast footage of him meeting with Gaddafi in that capacity at the time.

His companies are also linked to the Iraqi Oil for Food scandal, during the embargo on Saddam between 1990 and 2003.

Abduljalil Abdulhak is Shaher's younger brother. Currently, he is executive manager of the Shaher Trading Company and chairman of the Coca Cola company in Egypt, Yemen and Libya, according to information attached to the registration details of offshore mirrors.

Ali Abdullah Saleh's ousting eroded many of the privileges given to the Abdulhak empire. Legal cases began to emerge against their interests, including by the National Anti-Graft Commission, over tax-evasion allegations related to the MTN telecom company in which the family owns shares.

With Saleh now in cahoots with the Houthi rebellion that has ousted the internationally recognised president and his administration from Sanaa, it remains to be seen whether the Abdulhak brothers will weather the storm of the nation's civil war - and how solid the foundations of their empire will remain when the violence has eventually ended.

Original Arabic investigation by Mohammad al-Mahdi.

Translation and additional writing by Karim Traboulsi

|