Testing the Turkey-Qatar military partnership

The factory was established in 1975 in the northern city of Sakarya on around 1.8 million square metres of land. It employs about 1,000 workers and is estimated to be worth $20 billion.

On 13 January, it was announced that private defence company BMC will run the factory under a new arrangement for the next 25 years. BMC is run by businessman Adham Sancak who occupies a seat on Turkey's AKP's executive board, and is known to be very close to President Erdogan. Sancak bought the company in May 2014, and shortly after, Qatar's armed forces became a critical player, when it bought 49.9 percent of the company.

Over the last 44 years, the Turkish military factory has manufactured different types of military equipment including artillery, howitzers, ammunition carriers and tracks for tanks and other military carriers, and was also responsible for modernising the Leopard 1, 2 tanks among others.

Privatising the factory drew a wide range of criticism from different parties including the main opposition parties and the Türk Harb-İş defence industry workers' union.

Government officials responded to these critics by stressing that the factory had not been sold, rather the production rights were transferred to the new company for an agreed period.

|

Privatising the factory drew a wide range of criticism from different parties |  |

Turkish defence minister Hulusi Akar visited the factory and assured the workers that, "Our goal is to increase the productivity of the plant, to upgrade its technology and enable it produce strategic goods and export to friendly and allied countries."

In recent years, the Turkish government has pursued aggressive policies to speed up the development of the country's indigenous defence industry. Beyond sending a message of Turkey as a rising power, the policy has at least three main goals.

First, to decrease the defence industry's dependency on foreign players, while also moving to modernise the army. Second, to save money and increase the contribution of the sector to Turkish exports and the country's GDP. And third, to establish Turkey as a leading arms exporting country.

Data collected from Turkish Exporters Assembly (TİM) and Defence and Aerospace Industry Exporters' Association (SSI) shows that the industry has performed quite well over the last decade.

|

|

| Turkish-Qatari cooperation on show at DIMDEX 2018, the International Maritime Defence Exhibition and Conference in Doha, Qatar [Getty] |

Exports in the defence and aerospace industries rose from $196 million in 2004, to around $1.8 billion in 2017. The year 2018 witnessed a 17 percent increase in these exports in comparison to 2017, breaking the $2 billion threshold for the first time.

According to official statements, Ankara managed to reduce the country's external dependency in the defence industry from around 80 percent in 2002, to around 35 percent today. A 2018 report for SIPRI categorises Turkey as an "emerging producer" with the ambition of amplifying arms-production capabilities in naval, air, land, electronics and ammunition production.

According to the report, electronics producer ASELSAN, and Turkish Aerospace Industries (TAI) both occupied a respectable position on the list of the top 100 global companies for arms sales in 2017.

|

Ankara managed to reduce the country's external dependency in the defense industry from around 80 percent in 2002, to around 35 percent today |  |

Despite this progress, the government is a long way from reaching its ambitious goals for this sector.

As stated by Ismail Demir, the head of the Presidency of Defence Industries, the government's strategic aims are "to make the Turkish defence industry 100 percent independent by 2053, increase its export capacity to $50 billion, and have at least 10 Turkish defence companies among 100 biggest companies in the world".

This sort of growth would put Turkey in a completely different league, but in order to strive for such progress, investment is desperately needed. Given the recent problems with the Turkish economy, this serious obstacle could easily hinder Ankara's ambitions, and disrupt its strategic plans.

On this particular issue, Qatar is expected to play an important role, however Turkish opposition is questioning Doha's part, warning that the implications might be serious for Turkey's national security. From the government's perspective, bringing Qatar to the table is designed to keep other countries that may pose a threat to Ankara's security away from this crucial sector.

|

|

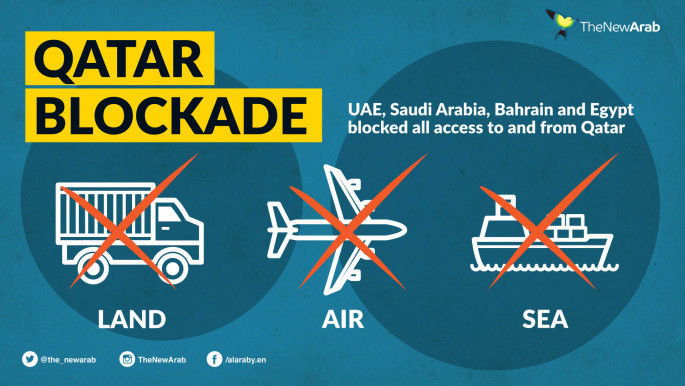

This partnership is vital for the both parties. The 2017 blockade of Qatar shed light on the emerging defence relations between Ankara and Doha and proved to Qatar how valuable its relation with Turkey was. Ankara, for its part was critical in preventing the military escalation of the crisis, as both Riyadh and Abu-Dhabi reportedly had plans to invade Qatar.

Since the blockade of Qatar in 2017, Doha has spent more than US$25 billion on military procurements. In this sense, Qatar has demonstrated its potential for expanding its military capacity; another reason for Ankara to eye a bigger share of Doha's arms procurements.

Speaking at the BMC Production and Technology Base ceremony on 13 January, Erdogan said "we expect this facility to provide an added value of US$5 billion annually to our country. Apart from our own needs, we plan to export about US$1 billion [worth of products from the new factory] to different countries, especially Qatar".

|

This partnership is vital for both parties |  |

Although Qatar has purchased several aerial and naval systems from Turkey in the past, military procurements increased markedly after the Gulf blockade of Qatar.

At the 2018 International Maritime Defence Exhibition and Conference (DIMDEX) in Doha, Turkey's defense firms such as Baykar, Nurol Makina, BMC, Anadolu Shipyard and others emerged as big winners, signing deals worth approximately US$800 million with Qatar.

Moreover, while ASELSAN agreed on a joint partnership project with Doha's BARZAN holding under the name BARQ, Turkey has been commissioned to establish a naval base "Borouge" for special operations in Qatar.

In November 2018, the state Defence Industries Presidency (SSB) and BMC signed a multibillion-dollar contract for the serial production of the Altay, Turkey's first and long awaited new-generation battle tank. Initially, 250 tanks are to be be produced, with an advanced version to follow.

While BMC was granted a series of state 'super incentives', there are doubts over the Turkish- Qatari firm's capacity to deliver what is required in the right time frame.

In addition, the lack of adequate engines needed for the Turkish-made tank could complicate the production process, and even cast doubt on the future of the programme as a whole. In this sense, BMC will be the first real test for the Turkish-Qatari military and defence partnership.

Ali Bakeer is an Ankara based political analyst/researcher. He holds a PhD in political science and international relations. His interests include Middle East politics with a particular focus on Iran, GCC countries and Turkey.

Follow him on Twitter: @alibakeer

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author, and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.