Young lives ended by police brutality: State impunity must end now

Young, working class people rioted, directing their anger, frustration and disgust at this injustice, towards the police up and down the country.

This was not, however, a one off, and nor is it a case of 'a few rotten apples'. Since 1990 over 5,600 people have died in state custody; 1,061 of those deaths were in police custody. The numbers are shocking, but what makes it even more so, is that there has been not one conviction of an officer in a criminal court.

This summer again, Edson da Costa, 25, Darren Cumberbatch, 32, Rashan Charles, 20 and Shane Bryant, 29 all died after contact with the police. Cumberbatch, Charles and Bryant died within two weeks of each other.

These young black men had their lives ahead of them, but instead of being in the presence of their loved ones and building a future, they have joined the growing list of 500 people of colour, dead at the hands of the state in just under three decades.

Eighteen years ago, the Macpherson Report, which followed an inquiry into the Metropolitan police's investigation of the murder of a black teenager, Stephen Lawrence, brought the debate surrounding institutional racism in the police into the mainstream. It highlighted what is unfortunately still a structural reality today: The tragic failings of the state when it comes to black lives.

|

The inquest into Burrell's death stated that prolonged restraint by officers as well as their failure to provide medical help contributed to his death |  |

In 2014, as the Black Lives Matter protests in Ferguson gathered strength, many of us in the UK were inspired to follow the wave of actions. Several protests took place in London with thousands of people who shared the sentiment that police violence and brutality had to stop - not only in the US but also here in the UK.

In the absence of indictment for the US police officer who held Eric Garner in a chokehold that led to his death, a "die-in" protest was held at Westfield shopping centre in west London.

Despite it being a peaceful stunt, police kettled and arrested 76 people. Activists spent the whole night travelling between police stations where arrestees were being held. Many of them were young teenagers taken to stations far from the site (and their homes), and released in the early hours of the morning, with little access to public transport.

Furthermore, many also joined the rally by families who lost loved ones at the hands of the state, organised by the United Families and Friends Campaign (UFFC), who have long been campaigning for truth and justice.

As a young person growing up in Birmingham, I would join the annual demonstration led by Kingsley Burrell's family members. He died at the age of 29, four days after being sectioned by the police. The inquest into his death stated that prolonged restraint by officers as well as their failure to provide medical help were contributors to his death.

Every year, despite dwindling numbers and a lack of justice served, there would be an overwhelming police presence supposedly providing "safety" and "protection" to a mostly Afro-Caribbean march. Having attended many protests in the city, from Palestine solidarity to Free Education and anti-cuts, their presence always felt disproportionate.

There is something especially obscene about the way protests against police violence - as well as those families desperate for recognition of responsibility from the state - are handled. Attempts to intimidate protesters, and to dissuade any direct action demanding an end to state violence are nothing new. But given the context of the demands of loved ones, friends, and neighbours, they leave an especially bitter taste.

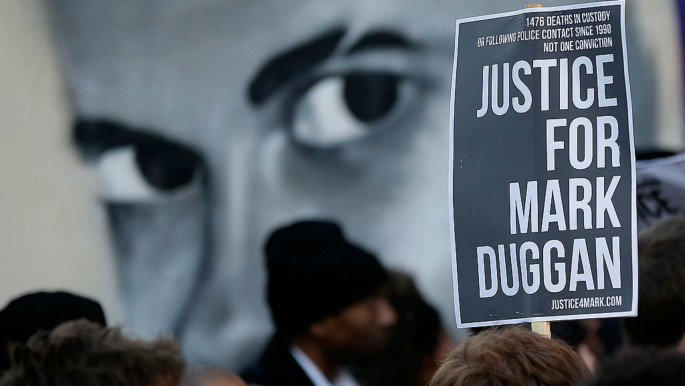

Similarly, attempted character assassinations of victims - as in the case of Mark Duggan - as well as the demonisation of their families and supporters, like in the case of the Justice for the 96, are now, disturbingly, the norm.

Instead of justice, appropriate sentencing of those responsible, and open and honest apologies to the families, the state offers nothing but more violence, provocation, and insults. In those circumstances the anger and the frustration felt by so many across the UK - especially black and working class communities - comes as no surprise.

|

Each campaign's victory increases the pressure and weakens state impunity |  |

Justice campaigns, attempting to hold the state to account for the countless deaths in prisons, immigration and psychiatric detention as well as police custody, are often long and painful processes for the families involved.

After the direct frustration and disgust dies out, the families and friends are left with the silence, and the emptiness of those taken too soon.

UFFC organise an annual rally and procession in Trafalgar Square on the final Saturday of October to offer a place for these families to come together and break their isolation. The occasion is a chance to raise the broader question of systematic and structural racism and immunity from punishment when it comes to police violence and killings. Protestors commemorate the lives lost and continue to demand justice - so far still denied.

| Read more: Out-of-control: 'Spit hoods' and police racism | |

These gatherings help families continue their fight, while also allowing others to show solidarity, and shine a light on the structural and institutional nature of the problem.

From raising money, to press support and coalition building, many justice groups need volunteers who are willing to help spread the word about their efforts. There are civil liberties groups such as Defend the Right to Protest and police monitoring groups like the London Campaign Against Police and State Violence which you can join.

But beyond that, there is a broader need for trade unions, student, faith and neighbourhood organisations, as well as concerned individuals to strengthen existing campaigns.

As shown by the recent charges brought against former senior police officers over the Hillsborough disaster, these campaigns, although they can take decades to achieve their goals, do more than offer a degree of recognition for those who survive: They shine a light on the lack of care for the lives of ordinary people - especially people of colour - the police, the press, and politicians can have, and how quickly the violence meted out against us can be normalised.

The campaign also shows that when a broad movement brings together groups and people from across society, justice can be achieved. Each campaign's victory increases the pressure and weakens state impunity. It also makes it a little harder for the next death to go unpunished, or even to take place.

As the famous slogan goes: If they don't give us justice, then we won't give them peace.

Malia Bouattia is an activist, the former President of the National Union of Students, and co-founder of the Students not Suspects/Educators not Informants Network.

Follow her on Twitter: @MaliaBouattia

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.