Why Iraq's courts aren't recognising IS crimes against the Yazidis

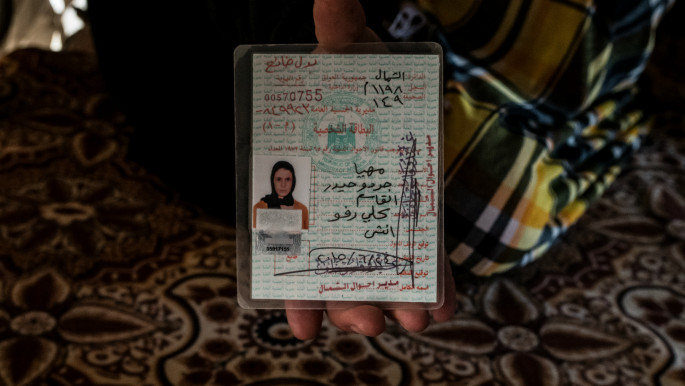

In what the United Nations described as a genocide against the Yazidis, thousands of members of this religious minority were enslaved, raped and slaughtered when IS stormed their ancestral homeland of Sinjar in August 2014.

Despite overwhelming evidence of the atrocities carried out by the group – including social media posts and videos in which IS members bragged about buying and selling women – to this day, almost no one has been held accountable in Iraq for specific crimes against the Yazidis.

Rather than bring charges for offences listed in the criminal code, such as rape or murder, Iraq's judicial authorities have been prosecuting suspects solely for membership in a terrorist organisation.

It's a more efficient way of building and prosecuting cases, explained Akila Radhakrishnan, President of the Global Justice Center.

"I think there's definitely been a push towards let's get them prosecuted, let's get them in jail," said Radhakrishnan. "Proving membership in a terrorist organisation from an elements perspective is much easier to do than for a particular crime."

|

|

According to a 2018 analysis by the Associated Press, Iraq has detained or imprisoned at least 19,000 people on terrorism-related charges since 2013. Prosecuting that number of people would be a massive undertaking for any country, much less one that just emerged from a bloody and costly war.

"The judges try to do their work as fast as possible because there's a lot of pressure," said Dr Zyad Saeed, an Iraqi lawyer who advises and trains other lawyers handling terrorism-related cases.

"A judge in an international court sees one case per year," Saeed said. "Iraqi judges see 150 cases per day."

Given the sheer number of cases, Iraqi judicial officials argue it's simply not feasible for the country's overwhelmed and under-resourced courts to gather evidence of specific crimes.

"The response that we make to that is you shouldn't have 19,000 men in prison," said Belkis Wille, senior Iraq researcher at Human Rights Watch. "You are prosecuting people who don't need to be prosecuted."

|

These are specific crimes... If they go unpunished, it sends a message to the perpetrators and also to the victimised community that the justice system does not serve them |  |

Despite concerns raised by human rights groups over the mass incarceration of IS suspects, Iraq has doled out thousands of convictions under its vaguely worded counterterrorism law, which prescribes the death penalty for anyone who commits or assists in a terrorist act.

That catch-all language doesn't differentiate between IS fighters and those who merely acquiesced when their cities fell under IS control. An IS garbage collector could easily get the same sentence as someone who enslaved and raped a Yazidi woman.

"These aren't the people that should be taking up the time of judges in courtrooms," Wille said.

Critics of the Iraqi government's current approach to prosecuting IS suspects argue that when everyone is prosecuted under the umbrella of terrorism, the more serious crimes against Yazidis go unrecognised, preventing much-needed healing and closure in the community.

"These are specific crimes," said Pari Ibrahim, founder and executive director at the Free Yezidi Foundation. "If they go unpunished, it sends a message to the perpetrators and also to the victimised community that the justice system does not serve them."

Having studied law in the Netherlands, Ibrahim is helping provide legal resources through her organisation to Yazidi women who want to see justice in the courts. Most she says are interested in exacting an eye-for-an-eye style of revenge on the terrorists.

"When I say what is possible and what is not possible in the legal systems, generally survivors are quite disappointed," Ibrahim said.

|

|

| Read also: 'Their wounds must be acknowledged': What does the future hold for Yazidis who survived IS? |

If given the opportunity, Ibrahim says those same women would not hesitate to testify against their perpetrators in a court of law. But because Iraqi authorities are trying suspects for violating the counterterrorism law, rather than specific crimes, there is no role in court for the victims of those crimes.

It's not for a lack of Yazidis ready and willing to act as witnesses, says Ahmed Khudida Burjus, the deputy executive director at advocacy group Yazda.

"We are getting messages from hundreds of Yazidis saying 'we are ready to testify.' Show us where to go," Burjus said. "But there is nowhere. There is no door open for them."

In addition to gathering evidence at dozens of mass graves and kill sites in the Sinjar region, Yazda staff have conducted interviews with Yazidi witnesses to IS crimes. Burjus says his organisation has recorded nearly 500 testimonies, some over four hours long.

"We have information about IS, IS members and their crimes. But there is nowhere to submit it," Burjus said.

The creation of a special UN team designed to document IS crimes is an encouraging sign. The team, known as UNITAD, is gathering evidence of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide for possible use in Iraqi legal proceedings. In March, UNITAD forensic and legal experts helped exhume the first of more than 70 mass graves dug by IS in Sinjar.

|

As the Yazidis continue to plead with Iraqi authorities and the international community to deliver justice, some 3,000 women and girls taken captive by IS are still missing. Hundreds of thousands more remain displaced |  |

"This is a step forward, but at the end of the day, we have to ask, where will all this information go," said Free Yezidi Foundation's Ibrahim.

In the end, many Yazidis like Ibrahim question whether UNITAD will produce meaningful results given its mandate.

"It's only to collect and preserve the evidence, which we welcome, but we don't know what will happen next," Burjas said.

At issue is whether UN staff could even hand over evidence to Iraq, given the country's use of the death penalty and the UN's position that capital punishment is a grave human rights violation.

In a statement provided to The New Arab, UNITAD spokesperson William De'Athe Morris said the investigators will "share evidence in accordance with United Nations policies and best practices, and relevant international law."

Some legal experts have speculated the UN could make arrangements with Iraq to suspend the possibility of the death penalty for cases in which UNITAD's evidence is used.

Meanwhile, as the Yazidis continue to plead with Iraqi authorities and the international community to deliver justice, some 3,000 women and girls taken captive by IS are still missing. Hundreds of thousands more remain displaced.

When Ibrahim visits camps and shelters throughout northern Iraq, she meets with Yazidi women and girls who managed to escape IS slavery.

"All of the sudden, someone will pick me out and say, 'Hey Pari, I need to tell you that I saw my perpetrator.'" They provide details of what their captor looked like. Some have names and photos.

In the cases of foreign fighters, and with permission from the victim, Free Yezidi Foundation has shared the information with Western governments in the hopes the IS member will be tried in more reliable courts.

Recently, a 27-year-old German woman was put on trial in Munich in what's considered to be the first prosecution for war crimes committed against the Yazidis. But in Iraq, Ibrahim has lowered her expectations for accountability.

"I have very little trust in the system," Ibrahim said. "Justice is not a priority."

Elizabeth Hagedorn is a freelance journalist focusing on migration and conflict with bylines in The Guardian, Middle East Eye and Public Radio International.

Follow her on Twitter: @ElizHagedorn